Waiting for a Chinook

Early February is probably the toughest part of living in Montana. Its frigid cold, snow is piling up, rivers are icing over, and the cold north winds put us in -30F windchill territory.

If you have even a passing interest in western history, you have probably seen Charles M. Russell’s famous postcard “Waiting for a Chinook”. He painted this when he was working for the HO Cattle Company out of Utica in the winter of 1887. The forlorn image of a gaunted up old cow in deep snow being circled by wolves haunting. If you haven’t spent a winter in Montana (and no one here would argue with your sanity in that), you might wonder about a “Chinook”. What is that?

A little bit of background is in order. Wind is just part of the landscape out here – it seems like it’s blowing about 11 months out of the year. We’re used to them (not to be confused with actually liking them). We have fall winds, spring winds, North winds, all kinds of them. These are not breezes, we don’t bother with those. The National Weather Service increased the threshold for issuing high wind warnings from 58mph to 75mph in the past several years along the Rocky Mountains because at the 58mph threshold the warnings were commonplace – no one was paying attention to them anymore.

Our two most impressive winds are the Bora and the Chinook. The Bora wind originates in the Arctic Tundra in northern Canada. It gathers intensely cold air there, and when the jet stream drops into a big southern loop in the US it brings this Arctic blast of air with it. It’s particularly powerful along the mountains as it’s considered a ‘downslope’ wind, gathering energy from the prevailing western winds, scooping them up as it follows the mountains. This wind is often followed by high snowfalls along the mountain front but rarely pushes very far into the mountains. We’ve experienced this effect in the fall when we pack up for a hunt during an absolute blizzard at the trailhead. As we head into the mountains the storm abates completely within a few miles.

The Chinook winds are entirely different. The American Indians called Chinooks the “Snow Eaters”, for good reason. The air is so warm and moving so fast, that snow and ice vaporize instead of melting. It will remove about an inch of ice and a foot of snow in an hour. Watching this wind develop is quite an experience.

The Chinooks seemly come out of nowhere. You can actually here them coming, they quite literally sound like a freight train from hell headed straight at you. If you’ve ever been in an earthquake, it’s quite similar. There may be a gentle breeze preceding them, but there can be no doubt of what is coming when you hear the low rumbling off to the west. The clouds formations change to look like gigantic white bedsheets that are being shaken out, giving a rolling feel to the sky.

Then they hit with force. The first thing you notice is this serious. It will blow a horse over and it’s LOUD. Wind speeds jump almost instantly to 40mph, and often go much higher. Logan Pass in Glacier Park recently recorded gusts exceeding 125mph, and here in Choteau we have recorded wind speeds well over 100mph. That’s enough to roll 1500 pound hay bales casually across a field, tip over semi trucks, and rip roofs right off of barns and deposit them miles away.

The next thing you notice is that they are really warm. In fact, they are so warm that snow doesn’t melt – it evaporates. Ice goes from solid to gas before your eyes (a process called sublimation). It’s really weird to see. The air temperature can rise so quickly that glass will crack as it cannot acclimate fast enough to the temp change. The air temps will rise 40 or even 60 degrees in a few minutes.

It all sounds sort of crazy unless you experience it, but it is quite real and is caused by some unique conditions in our geography, and explained by the first law of thermodynamics.

Full disclosure – I took the thermodynamics series of classes in college but I did not care for it and did just good enough in those classes to pass. I’m not going to walk you through the math of this, but trust me that there really is a formula describing what happens here.

Stick with me because the way this works is fascinating.

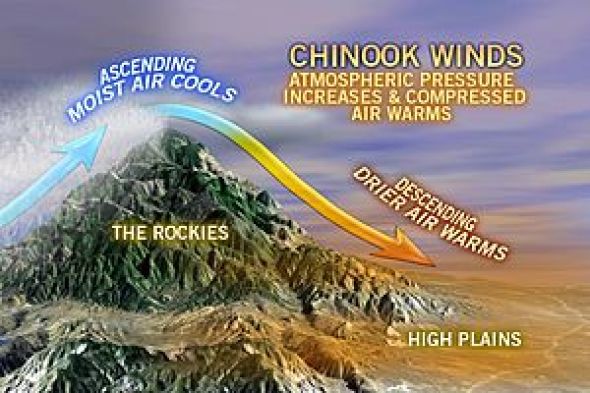

Chinook winds develop when warm, moist air blows from the Pacific Ocean in the Pacific Northwest towards the eastern mountain ranges. The air mass cools as it climbs the mountains, bringing rain or snow to the peaks (think BIG snow storms in the northern Sierras and the Cascades). It dumps all of its moisture on the west slopes as it goes. As the dry airmass moves across the Rockies it is compressed between higher pressure air above it and the Rockies below.

First is the thermodynamic part of the equation. Compressed air, particularly if it is compressed quickly, needs to have a place to exert that energy. If it cannot exert itself in some fashion then it stores the energy as heat. As the air moves across the Rockies to the east it is continually compressed – and gathers more heat. The heated air cannot expand against immovable forces above and below it.

Dry air has the ability to heat and cool with much more volatility than cold air (think the temperature extremes in a desert). This air has been compressed all along its journey, and reaches its peak compression AND temperature as it crosses the continental divide, which is maybe 40 air miles away.

Now comes the geographic part of the equation. Right after it crosses the divide, it experiences a critical geographic phenomena – the Rocky Mountain Front – which is the near abrupt termination of the Rockies. This amounts to a gigantic pressure release valve. If you’ve ever had a hot water heater pressure valve release, or seen a radiator cap release, you know what comes next.

The compressed, hot dry air now has a place to go and expands rapidly – very rapidly – towards the low pressure area below it. Pushed by the expanding airmass, vertical elevation drops, and heat dissipation, the wind velocity jumps dramatically as the airmass rushes toward the Great Plains. The air volume expansion and velocity releases enormous amounts of stored heat (energy) in the process.

The weather vane swings hard to the west, the cottonwoods shudder, the ice cracks violently, and the icy grip of winter lifts if only for a day or two.